9.2. (§) Random Forest¶

Note

This section is optional, and will not be covered in the DSM course.

One shortcoming of the CART model discussed in the previous section is that it typically exhibits high variance. This means that the model might change significantly if it were built on a different sample of data. In general we hope that our models are robust, and not highly dependent on the particular observations in the training set. Instead we prefer models that exhibit low variance, meaning the model parameters would not change drastically if we built the model on a different random sample of data.

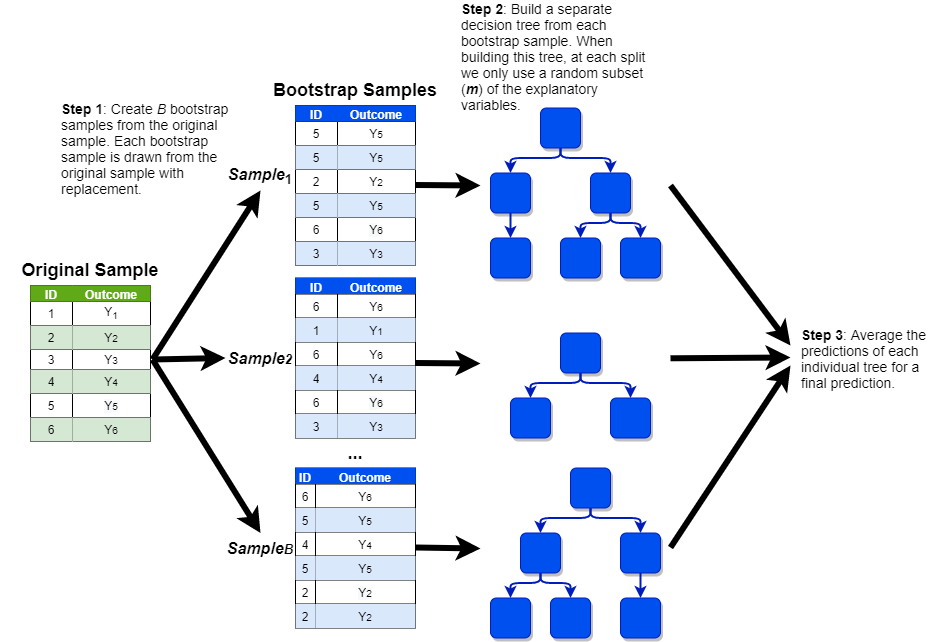

Statistical theory tells us that even if the variance of an individual model is high, the variance of many such models averaged together will be significantly lower. Of course, we usually only have one training set, so we do not have the luxury of building many different CART models on separate data sets and averaging them together. However, thanks to a technique known as bootstrapping, there is a way to build many different trees on a single data set. This model, known as the random forest, works according to the following steps:

Generate \(B\) replicates of the training data by randomly sampling from the training data with replacement. Each replicate should be the same size as the original data set.

Drawing a sample with replacement means that a given observation can be included multiple times in the sample. Imagine that we were randomly drawing a sample of bingo balls out of a hat. If we drew G7, we would record that value in our sample and then throw it back into the hat before drawing the next ball. This implies that we could potentially draw G7 again later on.

This process is called bootstrapping.

Build separate decision trees on each of the \(B\) samples, with one caveat. Instead of freely building the decision trees, there is one additional rule: each time we make a cut, consider only a random subset of \(m\) features from the full set of \(p\) features; a common rule of thumb is that \(m\) should be around the square root of \(p\).

In this example, we are training a random forest to predict

churnusing the twelve independent features in our data set (so \(p\) = 12). As the square root of twelve is 3.46, let’s think through the random forest model with an \(m\) of four. Each individual tree in our forest is built on one of the \(B\) independent samples that were drawn in the previous step. Every time a cut is made within each of these trees, the algorithm randomly selects four of the twelve independent features in our data set. As before, the cut is made based on whichever one of these four features minimizes the entropy (i.e., maximizes the information gain). For the next cut, another set of four features are randomly selected, and the process is repeated.

Make predictions for new observations by averaging the predictions of all of the trees together.

This process is shown in the visualization below (with a simplified sample of only six observations):

Just as the decision tree model can be used for both classification and regression, the random forest model can be used to predict discrete or continuous outcomes. We can fit a random forest model in R with the randomForest() function from the randomForest package, which uses the following syntax:

Syntax

randomForest::randomForest(y ~ x1 + x2 + ... + xp, data, ntree = 500, mtry, importance = FALSE)

Required arguments

y: The name of the dependent (\(Y\)) variable. If this variable is coded as a factor the model assumes you are trying to perform classification; if it is coded as a numeric, the model assumes you are trying to perform regression.x1,x2, …xp: The name of the first, second, and \(pth\) independent variables.data: The name of the data frame with they,x1,x2, andxpvariables.

Optional arguments

ntree: The number of trees to build in the forest (i.e., the number of bootstrap samples \(B\)).mtry: The number of variables randomly sampled as candidates at each split (\(m\)). For classification, the default value is the square root of the number of independent features (\(\sqrt{p}\)). For regression, the default is the number of independent features divided by three (\(p / 3\)).importance: Whether the importance of the predictors should be assessed. By default this isFALSE, but we will set it toTRUEso that we can observe the importance of each feature in the next section.

Below we apply this to the churn data set:

modelRF <- randomForest(churn ~ ., data = churn, importance=TRUE)

9.2.1. Feature Importance¶

Because a random forest model is comprised of many, many individual trees, we cannot interpret it as easily as we did with the CART model in the previous section. With the classification tree we built, we could visualize the tree and understand how the model made predictions. This is not possible with a random forest model, as each prediction is a weighted average of (typically) hundreds of different trees. How, then, can we develop some sense of how the model makes predictions?

One method that has been developed for random forest models is variable importance, which attempts to measure the relative importance of each independent feature (\(X\)) in the model. Following the process described below, each independent feature is ranked according to how important that feature is in predicting the target feature (\(Y\)). This allows one to develop a sense for which information the model is relying on to make predictions.

Feature importance is calculated according to the following steps:

Calculate the Out-of-Bag (OOB) score for each tree in the forest.

Remember that each tree in the forest is built on a bootstrap sample of the training data, which means each one of these samples is likely missing some of the observations from the training set. For example, in the visualization of the random forest in the previous section, the first bootstrap sample only contains observations 2, 3, 5, and 6; it does not contain observations 1 or 4. This means that for this sample, observations 1 and 4 are “out-of-bag” (i.e., not included). The OOB score for a tree is the prediction accuracy of that tree on its own out-of-bag observations. For the first tree, the OOB score is therefore the predictive accuracy of that tree on observations 1 and 4.

Randomly shuffle the values of the variable of interest. For example, if we were calculating the feature importance of

total_day_minutes, we would randomly shuffle thetotal_day_minutescolumn in our data set. Then, re-calculate the OOB score for each tree as we did in Step 1, but now with one of the columns shuffled.Calculate the final feature importance as the average difference between each tree’s two OOB scores, divided by the standard deviation of those differences.

Below we calculate the feature importance values for our model using the importance() function from the randomForest package, which uses the following syntax:

Syntax

randomForest::importance(x, type = NULL)

Required arguments

x: An model object created usingrandomForest().

Optional arguments

type: Either 1 or 2, specifying the type of importance measure (1=mean decrease in accuracy, 2=mean decrease in node impurity). We will usetype=1.

importance(modelRF, type = 1)

| MeanDecreaseAccuracy | |

|---|---|

| account_length | 0.5485722 |

| international_plan | 86.5958957 |

| voice_mail_plan | 19.6582028 |

| number_vmail_messages | 17.8299087 |

| total_day_minutes | 118.2393902 |

| total_day_calls | -0.3758706 |

| total_night_minutes | 9.3818798 |

| total_night_calls | 1.6974957 |

| total_intl_minutes | 32.5974654 |

| total_intl_calls | 44.9793176 |

| total_intl_charge | 33.3440245 |

| number_customer_service_calls | 74.8950187 |

This output indicates that total_day_minutes is the most important predictive feature in the model, followed by international_plan, then number_customer_service_calls, etc.